Effects of Nitrogen and the Various Forms of Nitrogen on Phalaenopsis Orchid-a Review

Beginner's Series 23 - Phalaenopsis Part iv

STEPHEN R. BATCHELOR

HUMIDITY is an elusive factor in orchid civilization. For phalaenopsis, its influence can hateful the deviation betwixt mediocre and superior plants and flowers. Growers of phalaenopsis under lights and in windows have to combat the natural tendency of indoor growing areas to be low in humidity. Without an almost continual replenishment of moisture in the air lost through heating and air conditioning, phalaenopsis may not thrive, though other factors in their civilization may be acceptable.

Humidity as the limiting cistron in culture is nearly impossible to testify conclusively, and nevertheless, for example, phalaenopsis sparsely arranged under lights and exposed to the dry air of a large, heated room volition indeed suffer to some extent. Growing in very dry out air, phalaenopsis may refuse to hold more than two or 3 flaccid leaves; whereas healthy phalaenopsis have at least four or v firm leaves at any 1 time. Plants attempting to flower under such weather take been known to driblet their buds. At the very least, those flowers which do open in dry air will not final about equally long as those experiencing proper humidity levels.

To increase humidity indoors, phalaenopsis growers need to provide a source of water open to the air, likewise as to limit the volume of air to be moistened. Large trays filled with porous gravel on which the plants can be placed, maintained with a shallow pool of h2o, can yield adequate humidity, if they only take to moisten a limited volume of air. Closing the door to a small "growing room" may sufficiently limit the air volume. But during periods of stress on humidity levels, such as during cold weather when the heat is on frequently, these trays may not be enough to maintain the 50-threescore% relative humidity recommended for phalaenopsis (Hager, 1978; Freed, 1976).

Humidifiers are more successful at increasing humidity indoors. Triggered past a humidistat, a humidifier will run when humidity levels take fallen below the desired, set level. Yet even humidifiers have limited capabilities, and for big, heated rooms they can end upward running continuously, never achieving the desired humidity during superlative periods of heating or cooling. Phalaenopsis growers with plants in larger rooms may find that only past enclosing the growing area in a tent of polyethylene plastic can plenty humidity be maintained. Some class of air circulation is all the more necessary if this is done. Air movement can be brought almost past a fan-driven humidifier aided by additional fans. Growers of phalaenopsis in basements may non take equally much a problem with humidity, though the lower temperatures which in function make possible higher humidity levels tin can piece of work against the phalaenopsis by slowing downwards growth.

Beginners should exist aware that humidity, like temperature, is to some caste a localized phenomenon. The plants themselves generate significant amounts of humidity through evaporation, both from their potting medium and their leaves. Considering of this, a larger, more densely arranged drove of plants will be less susceptible to low ambient humidity than a pocket-size drove of widely spaced plants. Closely arranging phalaenopsis, unfortunately, has the disadvantage of reducing the air and light reaching each plant.

Growers of phalaenopsis in greenhouses generally practise not have as hard a time maintaining adequate humidity. Nevertheless, indoor growers should take center, because they rarely if always take to suffer with the problems excessive humidity tin bring the greenhouse grower. In greenhouses, at that place are times when the relative humidity can reach 100%, the saturation signal, causing moisture to form on the plants and flowers. These are ideal conditions for Botrytis cinerea, which spots and ruins countless phalaenopsis flowers in greenhouses every year. Excessive humidity can likewise cause the spotting, or rot, of the plants. (More on this, and other issues in phalaenopsis civilisation, in the next article for this serial.)

WATERING AND FERTILIZING

Because phalaenopsis grow at a steady, constant rate throughout the year — given optimum light and temperature atmospheric condition — they need fairly consistent watering and fertilizing. This tendency to be in constant growth, in combination with their leafy constitute habit lacking the water-storage capabilities of bulbous, sympodial orchids, gives phalaenopsis the reputation for requiring frequent watering.

Watering frequency, yet, is non solely determined by establish and growth habits. Low humidity volition increase water loss through the leaves and potting medium, thereby increasing h2o requirements. Higher temperature and light conditions will have a similar event, necessitating more frequent watering. Conversely, low lite and temperature conditions will greatly reduce the water (and fertilizer) needs of a phalaenopsis, as such weather condition non just slow h2o loss only the growth rate as well.

Pot size besides greatly influences watering frequency. The larger the pot, the greater the reservoir of moisture surrounding the roots, and, consequently, the less often this h2o needs replenishing. For this reason, fully-grown phalaenopsis in eight-inch pots may only crave weekly watering even nether warm and vivid conditions. Seedlings in 2- or three-inch pots, on the other hand, are likely to need repeated waterings during whatever one week in order to maintain adequate wet at their roots.

Determining the corporeality of moisture in the pot at whatsoever 1 time is essential in deciding whether to water. Equally suggested with paphiopediiums, lifting the constitute in question is one of the all-time ways to determine the moisture atmospheric condition in the relevant interior of a pot. With exercise, a grower tin sense immediately when additional water is needed by the relative light weight of a plant in-pot.

Deciding how often to fertilize phalaenopsis tin exist a greater challenge for the beginner. The needs of any plant for the nutrients provided by fertilizers are, similar humidity requirements, very difficult to determine precisely. Ane factor to consider is the growth rate of the plants. Non all phalaenopsis abound at the same rate. Phalaenopsis seedlings can be very fast growing, and therefore may need more frequent fertilizing than older, more slowly growing plants. Phalaenopsis experiencing cool temperatures during the winter months may grow so slowly every bit to require little additional nutrients until night and day temperatures increase and significant growth resumes.

With the growth rate in heed, it is ordinarily recommended that phalaenopsis be given fertilizer every ane to ii weeks in the summertime and every three weeks to monthly during the winter (Freed, 1976; Noble, 1971). Poole and Seeley (1977), in their scientific studies of phalaenopsis seedlings under artificial calorie-free, found that a tiresome-release fertilizer, providing low levels of food with every watering, produced the best results. Hager (1978) cautions all phalaenopsis growers, however, to make sure the potting medium is moist before fertilizing, every bit phalaenopsis roots are especially sensitive and will burn at the tips if exposed to salt concentrations.

This susceptibility to impairment from salts is ane reason why information technology is by and large recommended that fertilizer be applied to phalaenopsis only in the form of a dilute solution. H2o-soluble fertilizers, themselves mixtures of nutrient salts, deliquesce readily when water is added. Used at the ordinarily recommended dilution charge per unit of 1/ii teaspoon of fertilizer per gallon of water, inorganic water-soluble fertilizers such equally the 30-ten-10 and 20-twenty-twenty formulas are safe and beneficial. Organic fertilizers such as fish emulsion (with a 5-5-1 formula) are also widely used for phalacnopsis.

Other facts support the recommendation that phalaenopsis be given merely light applications of fertilizer when in growth. Even the nearly rapidly growing phalaenopsis seedlings, when compared to other, non-orchidaceous plants such equally annuals, cannot be considered "fast-growing" in a broad sense. The occasional new leaf and gradually lengthening roots of mature phalaenopsis in growth would surely characterize them as the "snails" of the horticultural world. Dull-growing plants such as phalaenopsis simply do not require great quantities of fertilizer.

Also not to exist disregarded in forming fertilizing practices for phalacnopsis is the potting medium. The epiphytic media used for phalaenopsis are very porous and coarse when compared to the soil-like mixes used for other, more than conventional houseplants. Consequently, after the fertilizer solution runs through the potting medium and out of the pot, little fertilizer can exist expected to remain behind. The constitute gains the greatest benefit through straight absorption of nutrients from the solution applied, when information technology is applied. For this reason, frequent simply calorie-free fertilizing is thought to be advantageous. Many large-scale commercial and individual phalaenopsis growers apply extremely dilute fertilizer solutions every time they water by ways of adequately elaborate proportioners attached to their h2o sources. Without the flushing, or leaching activeness of plain water practical between successive fertilizer applications, though, a greater chance of damaging salt accumulation in the potting medium exists. Growers with small collections of phalaenopsis, and without precise proportioners, might be well advised to limit their frequency of fertilizing to "every other watering" — at most. In this way,the substitution of a dilute fertilizer solution will be both preceded and followed by a uncomplicated watering.

POTTING MEDIA

The type of potting medium used has a potent effect on the fertilizer and water needs of a phalaenopsis. Potting media vary in their capacity to retain water and nutrients. Osmunda, prevalent in orchid civilization before the 1960's, is capable of retaining large amounts of h2o, too as providing nutrients of its ain. Therefore, plants in osmunda required less frequent watering, and infrequent fertilizing — if at all. Osmunda is in virtually not-existant equally a potting medium today due to the limited quantities available and its high cost.

Today, fir bark, tree fern and sphagnum moss are the most ordinarily used potting media for phalaenopsis. With the exception of sphagnum moss, they are far less capable of retaining water and nutrients than osmunda, but vary considerably in these capabilities depending on the stage of their decay. Fir bark is a very dynamic potting medium. At first, bawl goes through a stage of rapid drying, even if wetted before utilise in repotting. Usually within a month subsequently repotting, the bark becomes "seasoned", or thoroughly moistened. In one case this is achieved, organic decay of the bark begins in hostage, with the proliferation of decay microorganisms which themselves require nutrients, peculiarly nitrogen. This disuse continues, and generally within two years the bark is reduced to fine-particled humus, a decay-resistant material capable of retaining large amounts of h2o and nutrients.

Because of this on-going decay process, phalaenopsis potted in bark and tree fern volition vary in their water and fertilizer requirements, depending on when they were last repotted. Recently repotted plants are likely to need more frequent watering and fertilizing than those which have been repotted for a year or more. A high-nitrogen, h2o-soluble fertilizer, such equally the 30-10-10 formula, is by and large used for phalaenopsis in mixes containing bark in lodge to compensate for the decay organisms' demand for nitrogen although a mounting body of show suggests that such loftier nitrogen fertilizers do more to accelerate the decomposition procedure than they do for improved growing of the plant and lower nitrogen concentration might exist a better option. Usually past the 2d year after repotting, disuse will have enhanced the chapters of an organic mix to retain water and fertilizer, and will have itself slowed down, thereby reducing the frequency of watering and fertilizing necessary.

Choosing the proper potting medium for phalaenopsis is perhaps a matter of trial and error. The best choices, notwithstanding, are made after considering the characteristics of the plant, the grower, as well as the potting medium. Phalaenopsis are sometimes potted in fine-grade materials considering of their high requirement for wet. A fine-grade mix does dry more slowly, being less porous. Just this reduced porosity has a significant drawback in that it greatly reduces the oxygen level of the mix — peculiarly when it is wet, all the more than and so when it has begun to decompose. Roots cannot function without adequate oxygen, and phalaenopsis roots peculiarly seem to require excellent aeration. Phalaenopsis potted in dumbo media oft produce roots which refuse to penetrate the mix, moving instead along the surface and over the side of the pot. With the majority of their roots outside the potting medium and pot, such plants are unduly exposed to humidity fluctuations. At the very least, they are awkward to water and fertilize. Many successful phalaenopsis growers use medium- and fifty-fifty fibroid-grade potting media for all only their smallest seedlings, and community pots. Ralph and Chicko Collins, who have a well-deserved reputation in the Northeast for being superb phalaenopsis growers, utilize a mixture of l% tree fern and 50% fir bark for their large drove. They utilize medium-grades of these two mutual materials for plants in 3- and 4-inch pots, coarse-grades for plants in 6-inch pots, and some "chunk"-grade textile for plants in 8-inch pots. With these more porous mixtures, watering in their warm and humid greenhouse is required one time a week for the larger plants. The Collins' sectional apply of nonporous, plastic pots helps avoid rapid drying.

Beginners may want to follow this example, specially if they are inclined to water and fertilize frequently, similar and then many of us. The porosity of a medium-grade tree fern and bark mix makes airless conditions at the roots unlikely, even just after watering, and encourages root growth. Coarse-course materials, nonetheless, might be avoided for all but the largest pots and plants, if the prevailing humidity is depression. Such high porosity could overexpose the roots to drying under these stressful weather. For this reason, as well, porous clay pots should be excluded from apply in growing phalacnopsis indoors.

REPOTTING

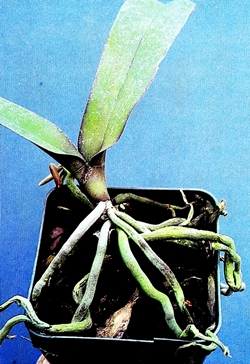

Whatever the class of materials when showtime used, the terminal decay of an organic potting medium makes repotting necessary, as the humus resulting lacks sufficient aeration for survival of phalaenopsis roots. Nevertheless there are other reasons for repotting phalaenopsis. While these monopodials do non abound over the border of the pot as many sympodial orchids do, they do grow taller to the bespeak that the region of the stem with the most active roots is above and out of the potting medium. Either of the two reasons mentioned here would justify the repotting of the phalaenopsis pictured in Figure 1.

Phalaenopsis roots are very often an authentic indication of whether repotting is necessary. The dying back of visible roots is a good indication at a glance that the plant is suffering (FIGURE 1). Only by unpotting the plant in question, though, can both the condition of the entire root system and the potting medium be determined (FIGURE 2). The bawl mix pictured in FIGURE 2 has been reduced to humus, and the airless conditions nowadays in the interior of the mix have led to the expiry of the roots once growing in that location. This lack of aeration towards the interior of the mix could also explain the trend of newer, still active roots to congregate along the inner-surfaces of the pot.

Live phalaenopsis roots are lite in advent, whereas dead roots quickly become dark and brownish (Figure 2). This easy distinction is very useful in the repotting process. Later the plant has been unpotted, and the determination to repot has been made, the plant should be cleaned of both decomposable potting medium and decomposable roots (Effigy 3). Once this has been done, a suitable pot can exist chosen which accommodates the root system comfortably (Figure iv). Mature phalaenopsis often need larger, 6-inch and even 8-inch pots because their root systems tend to be large, long and rather inflexible. Later on the appropriate pot has been selected, many growers add a bottom layer of gravel to enhance drainage (FIGURE 4). With the constitute properly positioned in the pot, such that the portion of the stem begetting the roots is below the rim (FIGURE iv), the premixed medium is added and gently pressed in and around the roots (FIGURE 5).

Phalaenopsis, similar many monopodials, can be divided along the vertical stem every bit one means of propagation. This tin can be done in one case the stalk has achieved sufficient length as to permit each of the resulting divisions to have adequate root systems. Figure three illustrates this betoken, only at the same fourth dimension is, unfortunately, misleading, every bit are the following FIGURES four and 5. Unwittingly, the lensman in the author got the better of the grower! There is no question that the tip-cut (meridian portion) of such a monopodial sectionalization requires repotting. Once cut and removed, information technology needs a pot of its ain. But, not but is the repotting of the remaining base portion, illustrated hither, non necessary, no experienced phalacnopsis grower would recommend it!

A tip-cutting of a phalaenopsis, with a healthy complement of leaves and roots, commonly continues to grow without relapse. It requires no special care, other than mayhap additional protection from extremes of calorie-free and temperature. The base section resulting from the division of a phalaenopsis, on the other hand, requires quite a different treatment. Without leaves and an agile growing point, and without the ability to manufacture food, it is in a precarious state. A base division of a phalaenopsis must draw on what stored free energy it has to initiate one of the dormant nodes on the side of its stem and resume growth. The terminal thing a grower should practice is to further shock a base of operations division past repotting!

Even in the example of the plant pictured, where the potting medium is largely decomposed, the base division is best left as undisturbed as possible. Farther decomposition of the root system is unlikely, if h2o is all but withheld. The water requirements of a leafless stem and root organization are minimal. Placing such a base sectionalization out of directly light, equally recommended, further reduces the need for boosted water. H2o should only exist given when some desiccation of the division is apparent (Freed, 1976). Under proper weather, there is a good take chances that within several months a dormant node volition activate, producing an offshoot. One time the offshoot produces several leaves, and roots a few inches long, it can be removed from the stalk, potted separately and placed in a protected location in the growing area.

The rooted base section of a phalaenopsis division, in this way, is used only as a vehicle for producing one or more, new plants. Information technology never once more becomes the main back up for a leafy pinnacle-portion. Even when the adjunct produced is mistakenly non removed, it grows its own root organization which supplants that of the base division (FIGURE 6). In any event, the base segmentation eventually declines and dies. Simply information technology is far more likely to practise so, quickly — and without producing a new plant — if it is repotted!

Other, more prolific and dependable ways of propagating phalaenopsis can be employed by the grower. Next month's concluding article will go along this discussion of propagation, and will devote some attention to the problems unremarkably encountered in growing phalaenopsis.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Freed, Hugo. 1976. Phalaenopsis are Easy to Grow. Amer. Orchid Soc. Bull. 45(5): 405.

- Hager, Herb. 1978. ABC of Phalaenopsis Growing. Amer. Orchid Soc. Bull. 47(12): 1096.

- Noble, Mary. 1971. You Can Grow Phalaenopsis Orchids. Privately published.

- Poole, Hugh A. and John One thousand. Seeley. 1977. Furnishings of Artificial Low-cal Sources, Intensity, Watering Frequency and Fertilization Practices on Growth of Cattleya, Cymbidium and Phalaenopsis. Orchids. Amer. Orchid Soc. Bull 46(10): 923.

Detect the top vendors in the orchid customs and their special offers on all things orchid.

If you are an AOS member, you lot also save 5% from every vendor.

2-Yr AOS members too receive over $600 worth of coupons from the Elite Market place Partners.

Special Resource

Discover great advice for watering, diet, lighting and more.

Source: https://www.aos.org/orchids/additional-resources/phalaenopsis-part-4.aspx

0 Response to "Effects of Nitrogen and the Various Forms of Nitrogen on Phalaenopsis Orchid-a Review"

Post a Comment